Can There Really Be Too Many Movies? In The Streaming Era, Maybe. – Deadline

In the mid-1980s, a common complaint among studio film distribution executives claimed there were just too many movies. What those moguls meant was that upstart independents, fueled by easy bank lending, junk bonds, and a seemingly bottomless well of home video revenue, were crowding screens with a sudden flush of, say, 450 films annually.

They didn’t like the squeeze. When Warner Communications acquired Lorimar-Telepictures in 1989 and closed its prolific movie division, I can even remember one Warner film executive explaining: “It was our turn to take one down.”

At the time, such thinking crossed my free-market, libertarian streak. Let a thousand flowers bloom, I said. The more the merrier! If all those companies (many of which quickly went broke) made too many movies, that meant more money for talent, and more entertainment for the rest of us.

But I’m beginning to wonder if the studio types didn’t have a point.

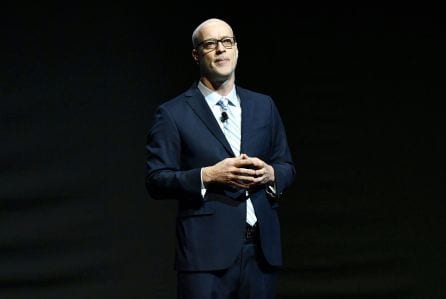

When Charles Rivkin of the Motion Picture Association of America and John Fithian of the National Association of Theater Owners present their annual ‘state of the industry’ talk at CinemaCon next month, an accompanying statistical report will probably peg the number of domestic theatrical film releases at more than 900—twice what it was when the chiefs were complaining. Boxofficemojo.com tracked 873 films last year, up 18 percent from 740 the year before, and the MPAA numbers have tended to run higher. That group’s 2017 report found 777 domestic theatrical releases. If its new tally is also up 18 percent, the grand total will be something like 917.

Of those, fewer than 100 will have taken in more than $25 million at the domestic box-office. The rest will live mainly on digital services, including streamers like Netflix, Hulu and Amazon. Well over half will have had less than $200,000 in ticket sales, meaning they went to digital aggregators without ever making a noticeable impression on the public.

Whether this is good, bad, or indifferent is hard to say. But it’s bound to become a factor when governors of the Motion Picture Arts and Sciences soon consider whether Oscar-qualifying films should meet a new, higher theatrical release standard, in order to separate them from small-screen, digital entertainment.

Certainly, nobody should, or could, be barred from making a movie just because no one wants to see it. (By that rule, some of my favorite movies would disappear. Just the other night I happily re-watched Sam Peckinpah’s Bring Me The Head Of Alfredo Garcia; and that one could hardly have done worse when United Artists released it in 1974.)

But there’s something to be said for the theory that a stiff level of resistance in the film business, a relatively high bar, makes everyone work harder to get over it. A film that has to win a following in theaters—or, at the least, has to win Roma-like promotional backing from a streaming service like Netflix—is going to give a whole lot more than passing thought to its audience.

The extra thought, effort, investment, pain and suffering—not some lucky magic—is what makes a movie an event. And that, I suspect, will be on more than a few minds when the Academy governors find themselves deliberating the impact of streaming, even as industry counterparts are explaining, at CineCon, that the digitally-driven number of releases is fast approaching 1,000.

Let’s block ads! (Why?)