T’s Fall Women’s Fashion Issue: The Tribe – The New York Times

OF THE MANY misconceptions about the fashion industry, the most persistent is that it’s glamorous. There are obvious reasons why this myth has not only endured but, thanks to Instagram, intensified: chief among them the industry’s apparent commitment to gamely fulfilling the public’s fantasy, in part by emphasizing the runway show — the 20 minutes of true spectacle that represent thousands of hours of unseen and unheralded labor — above all else. But anyone who has worked in or knows someone who works in fashion, from the humblest tailor to the starriest creative director, also knows that the business in fact bears a strong resemblance to the restaurant industry, another realm where the risks (and rate of failure) are high, the payoff is usually small, and in which dedication, talent, financial savvy and personality can be nothing against the vicissitudes of luck.

Among the many privileges this job has afforded me has been the opportunity to meet a number of artistic directors, the designers who helm a fashion house. And although they are distinct in their gifts, approaches and vision, the ones I admire all share a sometimes near-obsessive, touching (and decidedly unglamorous) interest in the actual material of fashion: the wools, the silks, the cottons, the nylons. Whenever I’ve met one for breakfast at ABCV — a restaurant in downtown New York — none have failed to examine the nubby Andean wool flat weave that upholsters the banquettes: trailing their fingers over it, musing aloud about how it was made and how it might have been dyed. Fashion may publicly celebrate the designers who understand how to make themselves into appealing characters, but it survives on designers who, at the beginning and end of their collections, want only to do the hard, lonely work of creation. Just as a chef’s place is, finally, in the kitchen, so, too, is an artistic director’s place in the studio.

And yet everywhere in the industry is evidence of the earthbound, the humble and the unexpectedly democratic. You are reminded daily of those thousands of hours of unseen and unheralded labor, but also of the improbability and fundamental modesty — as incongruous as that word might seem — of the people responsible for creating such confections. A good number of the people who populate the fashion business were, to some extent, outsiders: They were the picked-upon, the friendless, the lost. They came from small towns or from big families in which they never quite found their place; they knew from an early age that they were somehow — because of their sexuality or gender or interests or sensibilities — other, and as young adults, they set out to find the tribe from which they’d been separated. The industry feels tribal because it is: It has a tribe’s codes of dress and language and attitude; it is suspicious of outsiders; it lives to celebrate itself.

But it is also a tribe that, in theory, anyone can join. The entry fee is not your looks or connections (though the first one helps and the second one doesn’t hurt): It is how you see, and what you can imagine. Granted, it’s infinitely more accessible for some people, and granted, money can overcome almost any lack of natural visual acuity, at least for a period — but it also means that you can be a dyslexic boy growing up in Magherafelt, a small town in Northern Ireland, and go on to make clothes and accessories that upend every accepted code of luxury design and force a reconsideration of the elemental relationship between fashion and craft. Or it means you can come from a religious household in Texas, consider training for a life in the church yourself, come out in your 20s and, a decade later, find yourself at Schiaparelli as the first American to ever lead a storied Parisian couture house. In both cases, you will be under the age of 40; in both cases, you will create things that will challenge people to rethink the way they see fashion; in both cases, you will draw and draw and draw, letting yourself tumble down one wormhole after another. What will emerge will compel. But where it begins will be the same — a room with a sketch pad, a cup full of pens and pencils. It won’t be glamorous. But it will be true. And that, too, is what fashion can do — and what, at its best, fashion is.

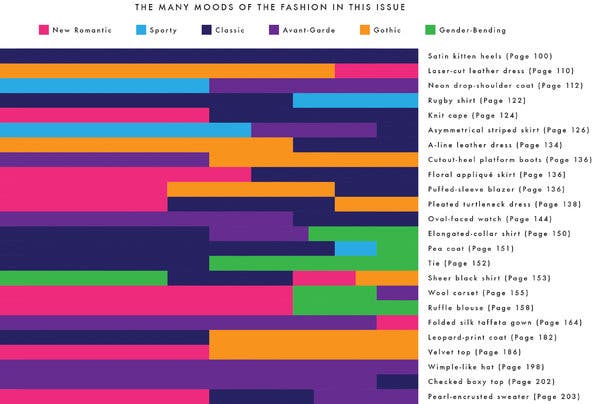

Read more from T’s Aug. 18 Women’s Fashion issue.

Model: Liza Makeeva at Next. Hair by Ramona Esbach at Total World. Makeup by Erin Parsons at Streeters using Maybelline New York. Manicure by Julie Villanova at Artlist Paris. Casting by Liz Goldson. Paris production: Rouchon Paris.

Let’s block ads! (Why?)